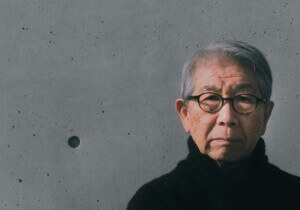

The Pritzker Architecture Prize has named Shigeru Ban its 2014 laureate. AN executive editor Alan G. Brake sat down with Ban at the Metal Shutter Houses, a luxury apartment building he designed in Manhattan’s Chelsea gallery district. He discussed influences from California to Finland, the social role of architecture, and what the recognition means for his work.

As a former Pritzker juror did you ever expect to be in the position of being a laureate yourself?

Not this soon. Also I know I have not made such achievements yet compared to other laureates, so I was not expecting it at all.

You are considerably younger than some of the other laureates; tell me where you see yourself in terms of your career.

I knew about the reason why I was chosen, and I knew that the reason was quite different from other laureates. It was an encouragement for me to continue to do the kind of social work as well as making projects like museums and others, so I try to keep a balance between other kinds of projects and working in disaster areas. So I’m taking it as an encouragement rather than the award was for such achievement.

How did you first begin working in disaster areas?

After I became an architect I was quite disappointed in our profession because we are mainly working for privileged people. Even historically this is the same, because money and power are invisible people with money and power hire architects to make a monument—to visualize their power and money for the public. I thought we could solve more for the public, for society, but it was not so. I thought there was an opportunity for me to use my experience, my knowledge for the difficult situations, like natural disasters—though I must say natural disasters are no longer natural. It’s our responsibility, and there were no architects working in disaster situations, because we are too busy working for the privileged. I’m not saying I’m not interested in making monuments, but, as I said, I wanted to use my knowledge and experience to help the people who lost their houses. And I thought we might make even better temporary housing. So the first time I started working in Rwanda in 1994 after the crisis, I proposed the idea of using cardboard tubes, paper tubes for the shelter construction for the United Nations High Commission on Refugees. I was contracted to develop this idea further.

Do you see other architects beginning to work in this field?

Especially in the Northern Japan earthquake and tsunami, many architects started working in the disaster area. But when I was working in Kobe in 1995 there was no one. Also, when I give lectures in many different countries, I get a good reaction from younger architects and from students. They are interested in our activities, they want to join us. The situation is changing.

Is that something that you feel is part of your role as an architect, to pull the profession more toward social issues or more toward everyday people?

Yes, yes, I do.

There’s a wonderful sense of invention in your work and every project is approached in a new way. Can you talk about how you begin?

Actually, I don’t invent anything new. I always use an existing material in a new way. Paper tubes are not a new material. In this building we have metal shutters. This is an existing material. So I try to use existing materials differently, with more meaning or more function, instead of just inventing something new. It’s also interesting, learning from context, using local materials. And I always look for a problem to solve through design, instead of making some sculpture.

How do you approach space or structure, some of the other fundamental aspects of architecture?

Even as a student, I hated to be influenced by others. Always there’s a fashionable style, Baroque, or neoclassicism, or postmodernism. I didn’t like being influenced by the fashionable style, the style of the day. But in history I looked at Buckminster Fuller or Frei Otto, they made their own structural system or developed their own materials to make their own kind architecture. I was dreaming as a student to make my own structural system, this is why when I started using the paper tubes, made of recycled cardboard, even concrete buildings can be destroyed by earthquakes, but my buildings made of paper tubes can be permanent. I thought by using weaker materials or humble materials I can make some different type of architecture, taking advantage of the weakness of the material.

With steel, it’s very flexible and strong. You can make any shape. With a paper tube, it’s so weak, and you can’t make just any form out of it. You have to find out what is an appropriate way of using it. Louis Kahn used to always ask his students, in his famous lecture, “Mr. Brick, what do you want to be?” And he said, “I want to be an arch.” So with the paper tube, which is a weak material, I have to find an appropriate way of using it. You can’t make everything from paper tubes. It’s not a perfect material. The limitations give me the idea to make an appropriate form out of this kind of material.

Looking back on your career thus far, what are the breakthrough buildings for you in terms of developing your thinking about architecture?

The Kobe project was kind of an important project for me, in terms of deciding my life’s work on disaster relief work, but I suppose for an architecture style or system, in the earlier period I designed a number of low cost houses, I called them “case study houses.” After I finished high school I came to the U.S. and the first school I went to was Sci-Arc in California. I fell in love with the so-called Case Study Houses, and Schindler, Neutra, Craig Ellwood, and so on. And I felt they had some Japanese influence. Because I didn’t study architecture in Japan, my first kind of Japanese influence came through those Case Study Houses. So in my early period I designed the so-called Curtain Wall House, the Walrus House, the Naked House, the House with a Double Roof. Many of these were low-cost housing with a special way of using an existing material or making a space connect to the inside/outside, so those case study houses helped to make my direction. Because before that I had some influence from Cooper Union, some influence from John Hejduk and the New York Five. But in order to get out from this movement from my school, I started to use the structure and development of materials to establish my own style.

So this interest and approach to materials has really been there from the beginning.

Yes, yes. Because in the beginning I was working on low-cost houses, I didn’t want to make a cheap house. So working with humble materials I could make something interesting instead of just making a cheap house with a low budget. That’s why I had some ideas of using everyday, low-cost materials differently.

You are now the seventh Japanese laureate. That speaks very highly of the culture of architecture in Japan. Can you talk a bit about what you draw from Japanese architecture culture and how you deviate from it?

First of all, I don’t know if I should be considered a Japanese architect, because I didn’t go to school in Japan and I’m working every where in the world, and also I’m not part of any school in Japan, and I don’t just mean universities. In Japan there are many schools, the Tange School, for example. And I didn’t work for any Japanese architects, except I worked for Isosaki for one year when I was a student. It was an internship almost. So I’m not part of this society. I didn’t have any public projects. The first opportunity came from France, the Pompidou Centre, and from the U.S., the Aspen Art Museum, and so all of those former Japanese laureates became very famous in Japan, they made public projects and then they started working abroad. But my case is different.

Why did you decide to study in the U.S.?

When I was in high school, when I was seventeen, I happened to see the Japanese architecture magazine A+U, they had a special feature on John Hejduk and Cooper Union, and I was amazed by his work. So that is why I came to the U.S., without speaking English. But there was no information, no internet, so I had to come to the U.S. to find out that Cooper Union does not accept foreign students. But I found out I could apply as a transfer student, so I had to look for a school I could enter and transfer to Cooper. I happened to find SCI-Arc. It was a brand new school, maybe three years old, founded by Raymond Kappe. It was very exciting how they renovated an old factory into the studio, so I applied, and I was very lucky to be interviewed by Ray Kappe. I didn’t speak English very well and he was very kind to accept me, and then after two and a half years I applied to Cooper Union.

What did you do after you graduated?

Well, I couldn’t graduate immediately because I had a big fight with Peter Eisenman, and so I had to extend my thesis. But I went back to Japan and began working for a very famous Japanese photographer, Yukio Futagawa, as his assistant. And I went with him to Europe, to visit Alvar Aalto’s projects, which I wasn’t interested in at all at Cooper Union. When I went to Finland to see Aalto it was a big shock to me; his use of local climate, of materials, his craftsmanship. Also, I organized an Aalto exhibition in Japan—and that was when I began working with paper tubes, because wood was too expensive.

What was it that was so eye opening?

The Villa Mairea. It’s in harmony with the climate, the context, and it takes advantage of many different kinds of warm materials, and also light. The light was so beautiful. But you know, in the International Style context was not so important nor was using natural materials, so Aalto’s was a completely different kind of architecture.

How did you get your first project?

After I finished at Cooper Union I wanted to go to graduate school in the U.S., but my mother asked me to design a small building for her boutique, so I decided to go back to Japan just to finish my mother’s building before coming back to the U.S., but I also organized three exhibitions, including the one on Alvar Aalto, which was brought from MoMA. And while I was doing these exhibition designs and working on the building for my mother, I started working on a small villa project and I became too busy, so I gave up coming back to the U.S. Also, it’s interesting in Japan, Japan is the only country, where even the middle class people hire architects to design even a small house. In a developing country or in a developed country, rich people hire architects to design big houses, but in Japan there is so much opportunity for young architects to design small houses. That’s really great training for us.

Obviously your interest in disaster relief housing has been very important to you and very important to architecture. What are some other areas where architects should be doing more?

I think in education. Many famous architects don’t teach, but I think teaching is very important. For me I had Raymond Kappe, Tod Williams, Ricardo Scofidio, Diana Agrest, Bernard Tschumi, John Hejduk. It was an incredible experience. And I can’t give them anything back, the only thing I can do is give the same thing to the younger generation. If I didn’t have great professors, I wouldn’t be here.